In my daily commute to work, I pass through Hamra Street, the heart of West Beirut’s commercial district and nightlife. International shops, such as H&M, Starbucks, and Caribou cafés, line the street alongside smaller local clothing stores, local pubs, and currency exchange booths. The Hamra district is Lebanon’s main medical tourism destination and the hub of Beirut’s countless private hospitals and medical laboratories. Though the spillover from the armed conflict in neighboring Syria and the fluctuating security situation in Lebanon have deterred many tourists, the neighborhood hotels and furnished apartments still profit from the effects of another regional conflict: an influx of Iraqis in search of health care.

Over the course of my daily wanderings, I have become accustomed to encountering scores of Iraqi patients and their escorts. On one of Hamra’s sidewalk benches there is a group of middle-aged Iraqi men chatting about lab results. On the other sidewalk across the street, a woman wearing the traditional Iraqi abaya (cloak) is pacing with her sick child. Farther up the street, near Starbucks, a couple of older men dressed in customary robes and ‘gal (headdress) unique to the city of Nasiriyah in the south of Iraq are asking for directions to one of the hospitals. A Lebanese taxi driver, one of dozens parked near small intersections and hotels stalking pedestrians, tells his colleague that he has to go pick up an Iraqi family with a sick family member. Farther down on the main street, two Iraqi men are pushing a wheelchair with a bald child, who is receiving chemotherapy at the local children’s cancer center. In Beirut, encounters with Iraqi patients have become troublingly familiar.

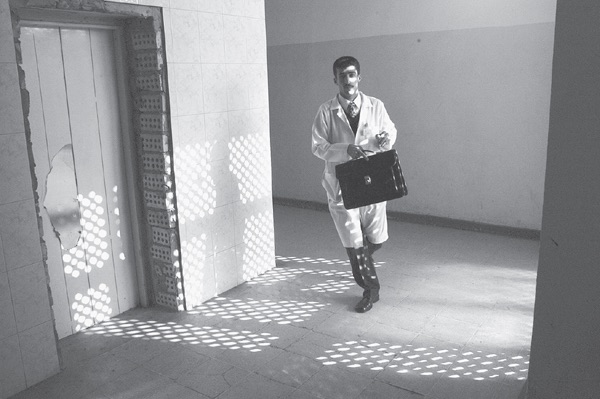

In Hamra, the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC)—one of Lebanon’s largest private hospitals—serves a wide range of Iraqi patients. Since the 2003 US invasion and occupation of Iraq, more and more patients from Iraqi cities are frequenting this 400-bed hospital. According to the hospital reports, Iraqis are the second largest national group (after Lebanese) comprising this hospital’s patient population. Similar trends are reported from other hospitals across the country. Located near the entrance of the AUBMC is an alleyway leading to the Weekend Hotel—a small seventy-bed inn with a quaint patio. It is just one of scores of small hotels, inns, and furnished apartment buildings dotting Hamra. Since 2007, most of the occupants of the Weekend Hotel have been Iraqi patients and their families frequenting Beirut for a variety of critical medical reasons. In the Weekend Hotel lobby, patients and escorts congregate daily to compare medical updates from the hospital, discuss recent news about events in Iraq, exchange wry remarks about politics, and share personal stories and experiences with others seeking care.

“Elhayat bil ‘Iraq ma’sat [Life in Iraq is a tragedy],” one chain-smoking escort declares while sipping tea with others in the lobby. He invokes an era of Iraqi prosperity with a blend of pride and defeat. “In the past, Iraqis used to come to Lebanon for tourism,” he says. “Now they come for treatment.” Next to him sits Abu ‘Adel, who had arrived in Beirut to receive his second round of chemotherapy. He explains that he visited a spate of doctors in Iraq before coming to Lebanon. He was first misdiagnosed, then given the wrong medications following incorrect lab results. “In Iraq, there is no state. . . . After years of war, dictatorship, and occupation, we lost trust in our medical system and doctors,” he explains, sprawled on the couch after a long and nauseating day at the hospital. “Most of the good doctors have left the country, and those who remain have lost their humanity.”

During the 1970s and 1980s, Iraq was celebrated internationally as a “success story”—an oil-rich socialist state achieving universal health care, expanding public health infrastructure, and promoting health among its general population. Doctors received rigorous training in Iraq’s internationally respected medical schools, well-equipped hospitals, and research centers. Students from around the region flocked to Iraq to study medicine, and patients from neighboring states traveled there to receive medical care. Today Iraq has become incapable of providing health care to citizens inside its borders, and Iraqis have become disenchanted with the state of their nation’s once-vaunted medical system and what many believe is the moral degeneration of the Iraqi doctor.

The phenomenon of patients leaving Iraq in search of health care became widespread after 2003, and took place across Iraq’s neighboring countries and their respective health-care systems.1 In addition to Lebanon, India, Jordan, Iran, and Turkey have also seen increasing numbers of medical care-seekers from Iraq. Moreover, successive post-2003 Iraqi governments have been actively outsourcing treatment of regular citizens, military and security forces personnel, parliamentarians—even members of the country’s various militia groups and political parties—to hospitals in Beirut and other regional cities. Still, the majority of patients travel at their own expense in hopes that their journeys will find the life-saving attention unavailable in Iraq. Families sell property and personal belongings, or borrow from relatives, friends, and acquaintances, to facilitate the necessarily frequent visits. Although tens of thousands of Iraqi patients seek medical care outside Iraq yearly, the state has proven incapable of restoring the country’s health-care system to the efficiency of its prewar years.

More alarmingly, Iraq’s medical enterprise has increasingly been implicated in the political violence and corruption that have plagued the country since the invasion.2 Since then, attacks on health-care professionals and establishments have become pervasive, and doctors have become the target of far-reaching, organized violence and humiliation.3 Hundreds of physicians have been murdered or kidnapped by militias and criminal gangs for ransom—some killed in reprisal for their past affiliation with the Ba‘th Party, others murdered as a means to further destabilize Iraq’s infrastructure.4 Numerous doctors have been assassinated in their homes or clinics. Others have been targeted with car bombs. In parts of the country, doctors refuse their government assignments or do not show up for their jobs because of insecurity and deterioration of hospital conditions, especially in Baghdad. Across Iraq, doctors have also been subjected to other forms of violence from patients’ relatives. Families and kin have taken matters into their own hands, mobilizing party militias or tribal thugs to negotiate with—and if necessary coerce—doctors to pay reparations for a lost life. Fearing retaliation for mishaps incurred during medical or surgical procedures, many doctors have refused to operate on patients.5 Unable to provide protection for the doctors even inside state-run facilities, the Iraqi government has allowed physicians to carry guns to their workplace.6 Those doctors who still work in Iraq are at risk and demoralized. Many have urged patients to seek care abroad, knowing that the post-2003 conditions of hospitals pose threats to both patients’ lives and their own.

The present state of disarray in Iraq’s health-care system does not date from 2003. The systematic dismemberment of the country’s medical infrastructure is a product of more than two decades of war and Western interventions, extending back to the US-led Gulf War of 1991 and international sanctions (1990–2003). The sanctions, more particularly, induced an alarming degeneration of the country’s health infrastructure and contributed to the exodus of thousands of doctors. Increasing numbers of senior specialists and junior doctors alike have escaped the country, contributing to the further shortage of physicians and expertise. It is estimated that close to half the medical force has escaped Iraq over the past two decades7—probably among the largest flights of doctors seen in recent history from one single country. This exodus of doctors is not merely the outcome of war and conflict-induced brain drain. Rather, it speaks to Iraq’s complex histories of colonial and postcolonial state building, dating back to the British Mandate (1920–1932).

Ungovernable Life is the first study to document the rise and fall of state medicine in Iraq. The following chapters chronicle close to a century of historical processes, movements, and shifts contributing to the engineering of Iraq’s health-care institutions and their eventual dissolution under decades of US-led wars and Western sanctions. The account offers a critique of common assertions about Iraq’s state-making histories and of Iraq’s dependence on repressive local forms of political rule. It suggests that since the inception of the state under the British Mandate, building the country’s medical infrastructures has been a defining feature of a productive mode of governance cultivated and instrumentalized by successive regimes of colonial and postcolonial rule. State medicine in Iraq has never been solely an Iraqi project but one entangled within and shaped by decades of relations with British medical institutions and other international bodies. The making of Iraq’s medical infrastructure has been part of transnational networks of knowledge, power relations, and state technologies and practices that politicians and technocrats employed to address a wide range of imperatives and to respond to crises threatening political and social order in the country.

My analysis of this history draws on insights from anthropological and historical approaches to medicine and science as regimes of governance enmeshed in contested colonial and postcolonial state practices and biopolitics.8 Here, I trace the shifting political role of the figure of the medical doctor across and through the epochs and terrains of Iraq’s statecraft.9 More than any other modern profession in the Iraqi nation-state, the doctor—through the management of national public health—has played a fundamental role in the modernization of the state and the operations of its governing apparatus. Since the inception of the British Mandate, Iraqi doctors have occupied a vital stage in state and nation building. Cultivated as an elite citizen, the doctor has been a vital actor in the normalization of the state in everyday life. Doctors were charged with the delivery of Iraq’s universal health care and the administration of urban and rural welfare. Throughout Iraq’s modern history, the doctor has also been a critical resource in responding to numerous crises. Medical practitioners have been mobilized to manage endemic and epidemic diseases, to respond to the fallout from development interventions, and to national mobilization at times of war.

Although a product of nation-state imaginaries, the training and professionalization of the Iraqi doctor has been a contested transnational endeavor—subsumed within processes of science and expertise dating back to the British Mandate. Since the inauguration of Iraq’s first national medical school in 1927, local doctors have studied under a meticulously designed British medical curriculum and have been supervised by both Iraqi and British authorities. Over the years, Iraqi and British governments sponsored thousands of Iraqi medical graduates to continue their specialization in the United Kingdom, to build expertise in medical fields, and to expand Iraq’s infrastructure. This transaction between Iraq and British health-care infrastructures would continue for decades after Iraq’s independence, and it would shape the foundations of institutional life and the career pathways of the country’s doctors. During the decades of war, sanctions, and occupation, this enterprise of science and patronage would eventually become one of the catalysts for the dismantling of Iraq’s health-care regime. During these years of uncertainty, thousands of physicians fled Iraq and sought security and career opportunities in the British metropole and its National Health Services (NHS), which to date hosts one of the largest populations of Iraqi medical doctors outside Iraq.

By tracing the global histories of Iraq’s state medicine and the shifting roles of doctors as agents of state, Ungovernable Life offers a fresh insight into the unfolding sociopolitical and infrastructure processes that have shaped the making and unmaking of health care as a form of governance in Iraq. The study delves into the historical processes of medicine and empire that have shaped living conditions during periods of warfare and state dissolution in the Middle East. It attempts to understand how imperial formations of governance, past and present, have intersected, been contested, and parted ways upon the terrain of medicine and state building in Iraq.

Displacing the Gaze

In recent decades, the story of the changing social geographies of health and disease has frequently been told through the lens of states’ liberalizing reforms to their health-care systems.10 It has been argued that the rise of neoliberal doctrine marked the beginning of a “new epoch” in post–Cold War state planning and social welfare practices across the North-South divide.11 The impact of this doctrine has been increasingly visible, materializing in the deregulation of state governance of the public good in favor of market forces or by moving the locus of governing outside the state.12 Such deregulation experiments have made states’ health-care systems increasingly vulnerable to corporate economies of bioscience, technology, and pharmaceuticals, especially in the global south.13 Moreover, the rise of humanitarian interventions and the global health enterprise have displaced the state as the sole provider of care, recast citizen bodies and populations in terms of their biological and therapeutic needs,14 and reframed the management of crisis-struck communities in terms of “bare survival.”15 In response to the undermining of social welfare projects, scholars have suggested that since the onset of this neoliberal “epoch” states’ modes of governance and everyday life have become increasingly defined by forms of “abandonment.”16 State retrenchment has become structurally implicated in strategies of rule, in which populations and territories are increasingly governed through ungoverning.17

Iraq tells a somewhat different story of state disintegration and ungovernability—one tied more intimately to the histories of colonialism, Western wars, and military interventions in the Middle East.18 Unfolding in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union, the 1991 Gulf War and UN-imposed sanctions on Iraq have systematically targeted and destroyed the country’s physical infrastructure and undermined its state health-care institutions. While declaring its aim to be the containment of Iraq’s war machine after its occupation of Kuwait in 1990, the US-led campaign deliberately targeted civilian as well as military facilities, with the aim of severing the “supply lines” on which the Iraqi regime depended.19 During the forty-day military campaign, more than ninety tons of bombs were dropped on Iraqi cities, targeting bridges, factories, roads, oil refineries, power stations, and water sanitation and sewage treatment plants. The US military used an array of high-tech weaponry, such as laser-guided bombs, and experimented with depleted uranium (DU) warheads to maximize the destruction of these vital targets. For the next twelve years, Iraq endured what has been described as one of the twentieth century’s harshest international sanctions regimes.20

The UN sanctions on Iraq were officially designed as a regime of “global governance” and as a containment program aimed at disarming the regime and preventing it from reconstituting its military capacity.21 The sanctions prohibited oil sales and banned imports of a wide range of consumer goods, medicines, raw materials, machinery, tools, and the spare parts needed to fix the country’s smashed infrastructure. The UN Security Council devised an exhaustive list of items that the Iraqi government was unable to import without UN approval. Items such as chemotherapy medications, batteries, and blackboard chalk were characterized as “dual use”—having a potential use for both civilian and military purposes. The UN Security Council further monitored the flow of goods to and from the country and carried out regular searches of Iraqi ministries and institutions. All states and international companies were obliged to enforce the ban and were prohibited from negotiating deals with Iraq without recourse to the Security Council.22 States across the global south—in Africa, Latin America, and Asia—structural readjustment programs were increasingly opening state prerogatives to the decentralizing forces of global markets. Iraq’s decade-long sanctions regime imposed a different dynamic: it isolated Iraq from the outside world and forced the gradual degradation of the state’s social and material infrastructure.

Curbing the Iraqi state’s capacity to restore its infrastructure has been described as an “invisible war” with detrimental consequences for the everyday lives of Iraqis.23 During the 1990s, public health reports pointed out that Iraq, once an effective developmental state, had become a “place of death and sickness.” By documenting the scale and scope of infrastructure destruction, such accounts pointed to the everyday suffering of ordinary citizens who bore the brunt of sanctions and the effective dismemberment of decades of state and infrastructure building. According to such accounts, the sanctions regime sent Iraq down a path of “de-development” deteriorating living standards. Reports of rising infant and maternal deaths, widespread food insecurity, and the deterioration of education, health care, and the environment were symptomatic of the “reversals” in development indicators.24 The sanctions regime, and the concomitant undermining of the state’s capacity to govern, further contributed to increasing state violence and brutality.

The US government saw the sanctions as a “failing” to contain the threats of Iraq’s authoritarian regime, and the events of September 11, 2011, became a pretext to conclude “unfinished business.” The US-led invasion of 2003 was waged under the dubious banner of the War on Terror in order to eliminate the regime’s “concealed” “weapons of mass destruction.” In the wake of the fall of the Ba‘thist regime, the occupation administration further dismantled state infrastructure by disbanding Iraq’s military and police forces. Concurrently—and perhaps consequently—the occupation was marked by the widespread looting of state property, deteriorating security, and eruptions of sectarian violence. Millions of citizens—especially middle-class professionals—were displaced, with close to 5 million Iraqis forced out of the country. Scientists, doctors, and professionals became targets for political assassinations, militia violence, and kidnappings. As the health-care system was overwhelmed by the deluge of those affected by the invasion and its aftermath, outbreaks of disease, epidemics, and fulgurations of violence followed.

Since 2003, media and political pundits have become accustomed to describing Iraq as “ungovernable,” using an increasingly familiar litany of tropes to diagnose the spiraling violence and political impasse: authoritarianism, occupation, sectarianism, tribalism, militarization, terrorism, ethnic tensions, et cetera.25 Iraq’s “ungovernability” has been similarly invoked in academic circles, through claims of the inherent fragilities of Iraq—a nation-state supposedly “carved out of the remnants” of the Ottoman Empire after World War I.26 Iraq, it has been argued, has been made ungovernable by imperial designs that have instilled coercive and spectacular forms of violence as a means of control—a tool, it is claimed, that successive Iraqi regimes used to instill fear and a semblance of order in its population.27 Alternatively, others have attributed the state of “disorder” in Iraq after 2003 to the nation-state’s inability to establish a “foundational myth” and achieve public consensus on its views of the past during decades of state formation.28 Iraqi society, it has been suggested, has normalized war under decades of conflict and Ba‘th Party rule.29 In such accounts, Iraq seems to have been made ungovernable by strong-willed and violent governments and the “divisions” of a society reawakened by the collapse of the thirty-five-year-old dictatorship of fear that held the country together.30

Such simplistic formulations of state making in Iraq could be attributed to ignorance. For decades now, social science research on Iraq has been stifled and fragmented, driven by a dearth of empirical evidence and narrow conceptions of state and society. Scholars working on the Middle East have often overlooked Iraq or studied it from a distance. This has been blamed on restricted access to the country as, since the 1958 revolution, successive regimes have been suspicious of foreign researchers.31 Others have argued, however, that “scholars of Iraq [in the West] have adopted many practices akin to those used in Cold War Sovietology, relying on a number of instrumental variables that are observable remotely. These include taking the discursive turn in examining the regime’s public rhetoric and the historical turn in examining the state’s colonial antecedents.”32 Given such systematic inattention and limited, if not flawed, research practices, the study of Iraq has often been “relegated to the margins of social science inquiry,”33 being “one of the most understudied countries in the world.”34

Since the 2003 US occupation and the demise of Ba‘th Party rule, research on Iraq has faced new limitations. The deterioration of everyday security has made the country a dangerous, if not impossible, site for Western researchers.35 Furthermore, the large-scale destruction of the country’s archives has undermined historical investigation.36 Like most researchers working on Iraq, I have faced myriad problems associated with limited access to the country and have struggled with the fragmentation and deficiency of available archives.37 When I started researching Iraq, however, I was perplexed by the dearth of critical analyses of the Iraqi state and the habitual focus on Iraq’s Ba‘th Party’s ideology, violence, and repressive state apparatus. As someone who had grown up, studied, and worked in Iraq as a physician, I found it difficult to reconcile this narrow conceptual framework of the state with the actual complexities of institutional life, and their potential for shaping how the state and the scope of its practices are seen. Although the Ba‘th Party’s security apparatus was an important instrument of political control, socialization encompassed other forms and processes of state legitimization and modes of governance. My focus on state medicine thus aims to sketch an alternative account of state making in Iraq—one more in tune with the changing relations of state power and its modes of rule. My analysis suggests that, given the country’s contested colonial and postcolonial histories, the regimes’ shaping of institutional life and population politics has been dynamic, multifaceted, and enmeshed in global processes of knowledge making and power relations. As I demonstrate throughout the book, medical discourses and practices have been central to the country’s architectures of governance. Medical schools, state hospitals, government ministries, and overseas educational missions have been sites where state building has been contested and subjects and citizens fashioned.

My criticisms of much of the writing on Iraq that comes from the global north is not only due to disagreement on what the Iraqi State was doing (or not doing). This book argues that new conceptual and methodological tools are needed to analyze state power and its breakdown under decades of US-led wars in the Middle East. Central to this endeavor is tracing and interrogating the different discourses and practices of governance that have imagined Iraq—its geographies, populations, and social institutions—as ungovernable and effectively made it so in swathes of scholarship.

This book demonstrates that discourses of Iraq’s ungovernability echo through the different articulations of state making that shaped the country’s colonial and postcolonial history. It is my contention that claims of ungovernability are neither mere representational forms aimed to produce an “Other” that is essentially unruly or primitive nor are they responses to modalities of local symbolic orders and alternative medical practices. Ungovernability goes beyond the logic and politics of designation, and is not merely a product of the liberalization of governance. I suggest that ungovernability is tightly enmeshed in the disordered operations of power or, in the words of anthropologist Michael Taussig, “in the tripping up of power in its own disorderliness.”38 In turn, I illustrate how articulations of ungovernability, and the responses to them, became the foundations on which architectures of rule and practices of science and medicine were imagined and deployed in colonial and postcolonial state making. My use of the dialectic of “governable” and “ungovernable” aims to open up new spaces in the analysis of the body politic where we see how regimes of power often produce that which they disavow.39 Such framing aims to think beyond the dichotomy of power and resistance, as well as recent formulations of governance within economies and zones of exception. My aim is to expand thinking about ungovernability as a feature of the internal dynamics and messiness of power as such.40 Here, I suggest that the imminent challenge to practices of power and the “will to govern” is predicated on the limits of its internal logics and practices—its own ungovernability. That said, I do not wish to reify ungovernability as a cultural form or a by-product of the particularities of Iraq’s state-making history. My treatment of biomedicine and power aims to avoid producing oppositions between modern medicine and cultural practices—as often happens in more traditional accounts in medical anthropology.41 My framing of power as ungovernable is an attempt to open up and gesture toward some of the internal tensions in the analysis of statecraft, and the refractions of those tensions through different periods of rule and across the dynamics of social institutions. Furthermore, building on the notion of ungovernability, I suggest that one can put together a specific genealogy of metaphors, practices, and careers that links the colony with the metropole and with other colonies—that one might follow people, technologies, and ideas as they move from one site to another. By thinking about the particularities of the Iraqi case and the recent unfolding of conflicts and state collapse in the Middle East, such analysis aims to provide a historically situated counterpoint to recent debates about the changing practices of governance in the so-called neoliberal epoch.

Colonial Disorders

Medical and scientific discourses about the colony as a “place of sickness” and “disorder” are deeply rooted in European and colonial histories and racialized encounters of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.42 Emphasizing the role of public health and hygiene projects in colonial governance, historians of medicine have further shown how narratives of colonial pathology were often instrumental in “colonizing bodies,”43 the molding of colonial subjectivities and race relations,44 and the control of the everyday conduct of colonizers and colonized.45 Although the British never officially “colonized” Iraq as they had India, discourses about Iraq as an “unruly place of sickness” trace back to the British military occupation during World War I and subsequent mandatory rule. Prior to the war, the British Empire had questionable intentions in the occupation of Mesopotamia—its term for the Ottoman provinces of Baghdad, Mosul, and Basra. Mesopotamia had been at the strategic frontier of the Persian and the Ottoman Empires for centuries, but disrupting the politics of the region was an expense no European power was willing to shoulder. During the nineteenth century, British interests in Mesopotamia were mostly confined to the desire to expand maritime trade. On a number of occasions, the East India Company tested the rivers of Mesopotamia as an alternative shorter route linking Europe and the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean and subcontinent. Such colonial adventures were limited by the fallout from the empire’s financial crisis and numerous anticolonial uprisings.

The three-year campaign to occupy Iraq arose from changes in the geopolitical landscape. Soon after the declaration of the war in 1914, and the Ottoman decision to side with Germany, the British Indian government landed a small military force in southern Iraq. The aim of the operation was originally to protect British interests in the Persian Gulf and prevent the Germans from seizing control of oil resources and water navigation around the region. London was reluctant, but the India government saw many benefits to advancing northward to secure the territories. As the occupying force advanced on Baghdad, it suffered a series of military setbacks and medical scandals. Attempts to reach Baghdad from the south failed abjectly after the Ottoman army laid siege to the British Indian force in the southern town of Kut al-‘Amara. British efforts to break the five-month siege failed, and disease and mutiny among the Indian soldiers contributed to the force’s surrender. In fact, more soldiers died from sickness than actual combat. Responding to what became known as the “Mesopotamian scandal,” the British opened political investigations and mobilized mobile hospitals and medical staff to the Mesopotamian frontier and strengthened supply lines to evacuate the wounded.

British accounts of the Mesopotamian campaign often invoked the harsh environmental conditions facing the military. British medical discourse depicted Mesopotamia as an ecology hostile to military occupation.46 Reports described Mesopotamia’s “notorious unhealthy climate, subject to the ravage of practically every known form of infectious disease in an endemic and epidemic form.”47 Military doctors analyzed Mesopotamian ailments from the framework of “tropical medicine.”48 British troops were put under strict medical and hygiene regulations.49 Still, commanders and personnel suffered a range of medical and psychological complaints, including heat stroke and exhaustion, cholera, malaria, as well as a range of inexplicable ailments that were seen as related to the country’s environmental and geographical conditions. For British officers on the ground, the success of any political project in Mesopotamia had to first reckon with health ailments and mobilize resources to control the threats posed by the local ecology. Colonial and medical officers in Mesopotamia reminded their superiors that the survival of any project depended on the expansion of health care and sanitation to the general population. The Indian government resisted any expansion of the civil administration, but Mesopotamia’s military authorities insisted on recruiting more British doctors and health-care staff to establish a comprehensive medical and public health administration that addressed the health of the local population. With mounting anti-British sentiments across the country, building Iraq’s new civilian health infrastructure was to be a means for absorbing popular resentment—one contrasting with British attempts to quell local uprisings through use of force.

One of the main concerns of British rule in Iraq after the war was management of medical crises as a function of sustainable state building. After the declaration of the British Mandate in 1920, tropes of Iraq’s hostile ecology gave way to the logic and practices concerned with expediting processes of state building and cultivating economic activity. With a relatively small civil administration, the tasks of the mandatory power in Iraq included the creation of a national government and institutions run by local elites under British supervision. Another task was ensuring the economic survival of the new state by integrating Iraq into the imperial economy. As a result, the British invested heavily in modernizing transportation infrastructure to facilitate the flow of goods and people in and out of the country. They opened new roads, laid down railway tracks, and expanded river navigation to cultivate the empire’s postwar economic recovery. On a discursive level, the tropes of tropical medicine gave way to the state-building narratives that then preoccupied medical establishments in Europe. British doctors in Iraq emphasized state welfare logics and the centralization of health-care infrastructure, and they called on the Iraqi government to focus on disease prevention and cutting down on economic waste.

Although such discourses represented a shift from conventional colonial medical narratives, they continued to be implicated in the broader processes of the empire’s postwar economic recovery. The earlier attempts to create an Iraqi Ministry of Health failed due to the lack of finances and British unwillingness to hand over public health matters to local doctors. Instead, a team of British and Iraqi physicians ran a modest Directorate of Health under the auspices of the Iraqi Ministry of the Interior that was, more or less, under British control. The directorate’s work focused on laying the foundations of the new state’s health policies and rationale. From the start, the directorate was charged with expanding Iraq’s health services and infrastructure, collecting and producing vital statistics, and reporting developments in the country’s health care to the British Civil Administration. It monitored the transportation systems closely and created a specialized unit to oversee health and medical matters pertaining to the expanding Iraqi Railways network. The work of the directorate was often challenged by lack of resources and required a more comprehensive system to contain the emerging threats of fast-moving epidemics. British doctors often argued with government elites for the need to centralize the country’s underdeveloped and fragmented medical structures. Due to the lack of central government finances, Iraqi officials argued for relegating the running and maintenance of peripheral health care to the provincial authorities.

The British saw centralizing Iraq’s health-care administration as necessary to the vitality of the new state and for governance under the rapid modernization of national infrastructure. Paradoxically, the enhanced mobility that resulted from the rapid upgrade of the country’s transportation network also made it possible for disease to spread more quickly. British concerns about the threats disease posed to Iraq’s fledgling state were exemplified during the cholera epidemic of 1923, which coincided with the annual Shi‘a pilgrimage to the holy sites of Karbala and Najaf. During the epidemic, British and Iraqi authorities confronted the shortcomings of simple quarantine procedures and the want of local resources to manage disease. The mobility of the pilgrims—thus the income of the holy cities—became dependent on the new transport infrastructure. Banning the pilgrimage that year would have had numerous political and economic repercussions, especially given the unrest in the south of Iraq following the 1920 anti-British revolt, which had been sanctioned by religious and tribal authorities. Managing the epidemic challenged the new state’s capacity to reconcile its economic and security priorities with those of public health. Unable to prevent the movement of pilgrims across the country, the directorate experimented with vaccines flown from India and drew on other imperial resources to carry out a door-to-door vaccination of the Karbala’s inhabitants and pilgrims both from inside and outside the country. Directorate activities and the mass production of the vaccine in the newly established central laboratory were further centralized in Baghdad. The successful and swift management of the epidemic was taken as a lesson in the importance of centralizing health-care administration in the capital. It refuted earlier arguments among Iraqi political authorities about the need to decentralize the country’s regional hospitals and dispensaries, both administratively and financially. The epidemic also reminded the authorities of the need to cultivate national resources to respond to imminent medical threats to the political, social, and economic orders.

Discourses and debates about Mesopotamia’s “unruly” environment underscored the fragilities of the colonial political order. They highlighted the limits of imperial structures in maintaining the health of British and Indian bodies under compromised British military control and in mobilizing medical resources to sustain the mandatory state in Iraq. As I aim to show throughout the book, such discourses of ungovernability often refracted through the practices of postcolonial statecraft. Moreover, the production of contested “pathologies” and “disorders” were often entangled with the political, economic, and technological interventions concerned with the engineering of the state, its environments, and its populations as a polity and a mode of social life.

1. Dewachi et. al., “Changing Therapeutic Geographies of the Iraq and Syria Wars.”

2. See Paley, “Iraqi Hospitals Are War’s New ‘Killing Fields’,” on the spiraling sectarian violence in Baghdad between 2006 and 2007, and its implications for the country’s health-care system. During these turbulent years, militias affiliated with the Ministry of Health kidnapped, imprisoned, and executed doctors and patients inside hospitals and government buildings. Militia members used ambulances to abduct citizens and converted the basement of the Ministry of Health into a torture chamber.

3. Al-Auwsi, “Iraq’s Doctors Are Subject to Humiliation and Murder.”

4. Al-Kindi, “Violence against Doctors in Iraq.”

5. Al-Auwsi, “Iraq’s Doctors Are Subject to Humiliation and Murder.”

6. BBC, “Iraqi Doctors to Be Allowed Guns.”

7. Burnham, Lafta, and Doocy, “Doctors Leaving 12 Tertiary Hospitals in Iraq, 2004–2007.”

8. My understanding of the connections among medicine, power, and state making draws on the insights and analysis of biopolitics and governmentality by Michel Foucault, see Foucault, “The Politics of Health in the Eighteenth Century”; Foucault, Security, Territory, Population; Foucault, Society Must Be Defended. Anthropologists and historians of medicine have used Foucault’s analysis to understand how science, medicine, and bureaucracy have been instrumentalized as regimes of government in colonial and postcolonial contexts, as well as in Western and non-Western settings. See Anderson, Colonial Pathologies; Arnold, Warm Climates and Western Medicine; Comaroff, “The Diseased Heart of Africa”; Stoler, Race and the Education of Desire; Brotherton, Revolutionary Medicine; Nguyen, The Republic of Therapy. Foucault proposed that one of the main mutations that shaped Western political organization during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was the increasing incorporation of life processes in the strategization and operation of state apparatus and institutions—what he called biopolitics or biopower. For Foucault, biopolitics is simply population politics (Fassin, “Another Politics of Life Is Possible”), seen, for example, in the rise of public health sciences, the management of epidemics and endemics, and urban planning and policing. Governmentality—defined as the conduct of conduct and associated with the rise of such biopolitics—denotes specific relations and technologies of power “linked to the emergence of the modern state, the political figure of the ‘population’, and the constitution of the economy as a specific domain of reality” (Lemke, Foucault, Governmentality, and Critique, 88). For Foucault, the effects of these technologies and techniques of governance fundamentally act on the body and its environment through discipline and control of the biological and social processes and relations of individuals and collectives—both within confined spaces and out in open territories. These are not necessarily repressive forms of power that govern through “domination,” rather productive ones “dispersed through society, inherent in social relationships, embedded in a network of practices, institutions, and technologies—operating on all of the ‘micro-levels’ of everyday life” (Pylypa, “Power and Bodily Practice”). Within such a conception, power’s main rationale and effect are the governing of “life itself” (Rabinow and Rose, “Biopower Today”; Rose, The Politics of Life Itself). In exploring the relationship between governance and life, I take the interpretation of Thomas Lemke regarding Foucault’s conceptualization of biopolitics, where “life denotes neither the basis nor the object of politics. Instead, it presents a border to politics—a border that should be simultaneously respected and overcome, one that seems to be both natural and given but also artificial and transformable” (Lemke, Biopolitics, 4–5).

9. I take my cue from anthropological work that has examined the critical role of medical doctors in the broader politics of state making and transformations. See Adams, Doctors for Democracy; Iliffe, East African Doctors; Wendland, A Heart for the Work; Good, American Medicine.

10. For examples of the consequences of neoliberalization on health care, see Kim et al., Dying for Growth; Han, Life in Debt; Keshavjee, Blind Spot; Farmer et al., Reimagining Global Health; Biehl and Petryna, When People Come First; Prince and Marsland, Making and Unmaking Public Health in Africa.

11. Many scholars have problematized positioning neoliberal logic as a universalizing force and have shown instead the intricate complexities and role of historical and local forces in shaping state practices across the globe. See Amar, The Security Archipelago; Collier, Post-Soviet Social; Ong and Collier, Global Assemblages for examples.

12. Collier, Post-Soviet Social.

13. Petryna, When Experiments Travel.

14. Nguyen, The Republic of Therapy.

15. Redfield, Life in Crisis.

16. Biehl, Vita.

17. Povinelli, Economies of Abandonment.

18. Recent accounts about war and violence in the Middle East have suggested that we have entered into a new era of contemporary warfare where military and humanitarian interventions are becoming increasingly intertwined. The efforts to rule through the mediation of military and humanitarian interventions are contained within technologies and techniques of governance that aims to “calculate the effects of violence and . . . harness its consequences.” As Eyal Weizman has poignantly argued, the will to govern under such logics is “grounded in the very ability to count, measure, balance and act on these calculations” (Weizman, The Least of All Possible Evils, 17). He further argues, “Inversely to make oneself ungovernable, one must make oneself incalculable, immeasurable, uncountable” (Ibid.) As I will show later, I present a different framework and genealogy of ungovernability, one that is tied to colonial history and framed as internal to the workings of regimes of power rather than being constituted in opposition to it.

19. In his famous piece on necropolitics, Achille Mbembe uses the First Gulf War as an example of infrastructural warfare where high-tech weaponry is employed in the interest of “shutting down the enemy’s life support” and doing “enduring damage of civilian life.” He argues that under such conditions of warfare, “Weapons are deployed in the interest of maximum destruction of persons and the creation of death-worlds” as “vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead” (Mbembé, “Necropolitics,” 40).

20. The impact of the war and sanctions on Iraq’s public health and medical infrastructure was much greater than that of other states under economic embargo in the 1990s, such as Cuba. In stark contrast to Cuba’s ability to maintain the integrity of its health-care infrastructure under sanctions, the First Gulf War and the consequences of sanctions on state medicine fomented infrastructure breakdown in Iraq. For the consequences of the economic sanctions and the collapse of the Soviet Union during the 1990s, see Brotherton, Revolutionary Medicine.

21. Gordon, “Economic Sanctions and Global Governance: The Case of Iraq.”

22. For the most comprehensive study of the UN Security Council sanctions in Iraq, see Gordon, Invisible War.

23. Gordon, Invisible War.

24. On the direct effects of sanctions on Iraqi society see Hall and Olafimihan, “A Dose of the UN’s Medicine”; Ascherio et al., “Effect of the Gulf War on Infant and Child Mortality in Iraq”; Gordon, Invisible War; Court, “Iraq Sanctions Lead to Half a Million Child Deaths”; Garfield, “Morbidity and Mortality among Iraqi Children from 1990 through 1998.”

25. There has been a wide range of Western media articles that have used the term ungovernable to describe the condition of violence and the failure to establish order in Iraq. See Reynolds, “Iraq the Ungovernable”; Ulhmann, “Iraq Close to Ungovernable”; Leader, “Ungoverned and Ungovernable.”

26. Bouillon, “Iraq’s State-Building Enterprise”; Dodge, Inventing Iraq; Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace.

27. Dodge, Inventing Iraq.

28. Davis, Memories of State. According to Davis, Iraq has been torn between two models of nationalism—pan-Arab and Iraqi. The absence of an acceptable model of political community has led to the failure to establish a collective identity.

29. Khoury, Iraq in Wartime.

30. Makiya, Republic of Fear; Sassoon, Saddam Hussein’s Ba‘th Party.

31. Farouk-Sluglett and Sluglett, “The Historiography of Modern Iraq.”

32. Ahram, “Iraq in the Social Sciences,” 251.

33. Ibid., 251.

34. Ibid., 253.

35. An exception to this dearth of critical work on Iraq has been the writings of anthropologist Hayder al-Mohammed, whose analysis of everyday life in post-occupation Basra has opened new avenues for theoretical and empirical research on the country. Based on prolonged ethnographic fieldwork, al-Mohammed has efficiently shown how—in the context of deterioration of security, militia kidnappings, and breakdown of the country’s infrastructures—everyday life in Iraq is predicated on ethical modes of sociality and dwelling that contrast with the somewhat flat representations in media and academia of social life in the country. See al-Mohammad, “A Kidnapping in Basra”; al-Mohammad and Peluso, “Ethics and the ‘Rough Ground’ of the Everyday”; al-Mohammad, “Ordure and Disorder”; al-Mohammad, “Towards an Ethics of Being-With”; al-Mohammad, “‘You Have Car Insurance, We Have Tribes.’”

36. The impact of the 2003 invasion on the destruction of the country’s archive has been well documented (see Khoury, “Iraq’s Lost Cultural Heritage”). Since 2003, however, there have been two main archival collections that have become available to researchers in the West. The first is the Saddam Hussein Regime Collection, housed at the National Defense University’s Conflict Record Research Center (CRRC) in Washington, DC. The second is the Ba‘th Party Records collection, housed at the Hoover Institution archive at Stanford University. These two collections have been highly politicized, as they were seized and confiscated by the US military and transported to the United States. See Montgomery’s description in “Immortality in the Secret Police Files.”

37. In lieu of the methodological challenges of such an undertaking, I have used myriad primary and secondary sources in English and Arabic to trace this history. I examined historical documents and collections at international universities and Iraqi research centers, and I conducted scores of interviews with different generations of Iraqi doctors and government employees both in Iraq and in exile. I read numerous autobiographical accounts of Iraqi doctors and other civil servants, as well as local historiographies of its health-care system. I have used accounts from different technical reports and academic articles from the periods I covered that pertained to the subject of my analysis. During my residence in the United Kingdom (2005–2006), I spent most of my time in London living with and interacting with different generations of Iraqi doctors and expats. The state of the country’s archive necessitated that I triangulate any available material to make better sense of the history, and I anchored my interpretation of the data in my own personal experience of growing up and living in Iraq for twenty-five years.

38. Taussig, Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man, xiii.

39. There is a long history of philosophical thought that draws from Kant, Nietzsche, Weber, Marx, and the Frankfurt school that has addressed internal dialectics of power. See for example Adorno and Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment.

40. Scott, Weapons of the Weak; Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed.

41. Here I take my cue from recent critical work in the anthropology of medicine that has problematized the notion of culture and suggested alternate frameworks that pay more attention to the materiality of the body proper and the way “culture, history, politics, and biology (environmental and individual) are inextricably entangled and subject to never-ending transformations” (Lock and Nguyen, An Anthropology of Biomedicine, 1).

42. Arnold, “‘Illusory Riches’”; Anderson, The Cultivation of Whiteness; Anderson, Colonial Pathologies; Mbembe, On the Postcolony; Moulin, “Tropical without the Tropics”; Said, Orientalism. Regarding nineteenth-century Europe, see Pick, Faces of Degeneration.

43. Arnold, Colonizing the Body.

44. Anderson, The Cultivation of Whiteness; Vaughan, “Health and Hegemony.”

45. Anderson, Colonial Pathologies.

46. Harrison, “Chapter 5, Wonder and Pain, Mesopotamia November 1914–May 1916.”

47. Great Britain. Colonial Office, “Mesopotamia: Handbook Prepared under the Direction of the Historical Section of the Foreign Office–No. 63,” 7.

48. The development of the field of tropical medicine in the West is one example of the history of colonial medicine. Tropical medicine has been linked to a 400-year-old history of European colonial encounters. It emerged as a set of knowledge and practices in the colony that were concerned with ailments and therapies specific to the “tropics” and other hot climates in Asia, America, and Africa. As others have argued, tropical medicine played an important role in shaping Western perceptions of distant lands and populations. It has also been instrumentalized in the control of local populations and in ensuring the survival of Europeans in alien environments. Moulin, “Tropical without the Tropics.”

49. In other settings, tropical conditions challenged the integrity of the “white” colonial body, and discourses about its imminent physical breakdown pointed to the limits of regimes of control. See Anderson, Colonial Pathologies; Anderson, The Cultivation of Whiteness; Rogaski, Hygienic Modernity.